Christmas is - and has long been - a predominately commercial holiday. In other words, it is marketed, increasingly early and more forcefully with each passing yuletide, in order to make people buy things.

Christmas is - and has long been - a predominately commercial holiday. In other words, it is marketed, increasingly early and more forcefully with each passing yuletide, in order to make people buy things.How can we become fully and truly human in a world plagued by violence, pain, sorrow, greed, exploitation, war, failure and death?

Friday, December 23, 2011

Christmas Reflections: Light only Shines in Darkness

Christmas is - and has long been - a predominately commercial holiday. In other words, it is marketed, increasingly early and more forcefully with each passing yuletide, in order to make people buy things.

Christmas is - and has long been - a predominately commercial holiday. In other words, it is marketed, increasingly early and more forcefully with each passing yuletide, in order to make people buy things.Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Should we still celebrate Thanksgiving?

Saturday, August 20, 2011

The Christ of Faith: The Face of God

I ascribe to a theology known as panentheism. To sum up this position briefly: I understand panentheism as the view that the term "God" does not refer to a separately existing supernatural and person-like being "out there" beyond us. The term "God" refers rather to reality at its ultimate level, "Being itself," "The ground of being," the all-inclusive whole. The best way to understand what these abstractions signify is through an analogy: We know from physics that reality has levels of being which require ever deeper descriptions of the same object. Take, for example, a table. At the level of human interaction the table is a solid object of such-and-such size, weight, height and so on. But at a deeper level of physical description the table is properly described as a certain relationship of interaction between fundamental particles. Both descriptions are correct, the latter simply describes the realty of the table at a "deeper" level.The panentheist takes this basic claim about the table and extends it to reality as a whole. The universe at the level of physical observation is the total collection of matter and energy interacting in space and time. If we go deeper, however, we can think of the universe as being reality itself only at a less than ultimate level of description. If we think of reality at its greatest or ultimate depth, we must think of it has having no boundaries or limits of any kind (after all what could limit it?). Ultimate reality would then be infinite (no limits), eternal (no beginning or end), and self-caused. All things in our universe can be seen as simply various expressions of the one ultimate reality at a level of less depth. Panentheists call ultimate reality "God" partly because it is eternal, infinite, and self-caused, but also because reality as a whole is so awe-inspiring, mysterious, and tremendous, that we can only feel reverence, humility, and awe when we contemplate it. In other words, for the panentheist all things are parts of God, but the reality of God goes deeper than reality at the level of things, though God does not exist apart from things as another being; God is, rather, the "ground of all being."

The suffering of Jesus and the failure of his mission is clearly part of this revelatory package too. In the brutal death of this man, his betrayel by those close to him, etc, we learn, clearly, that God is present - maybe even most present - in our moments of pain, sorrow, suffering, defeat, and loss.

I would add that in Jesus Christ God pronounces a final verdict on the choice human beings have made and continue to make for violence. But instead of inflicting violence on his enemies, God chose to absorb their violence in himself, in the one nailed to the cross.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Angry White Voters: The Truth about the Tea Party

Scholar Robert Putnam, best known for his study of American atomization in "Bowling Alone," has produced new data on the Tea Party and it's being billed as a shocker. Sit down before you read this: They are older, white conservative Christians "who were highly partisan Republicans long before the Tea Party was born."

Beginning in 2006 we interviewed a representative sample of 3,000 Americans as part of our continuing research into national political attitudes, and we returned to interview many of the same people again this summer. As a result, we can look at what people told us, long before there was a Tea Party, to predict who would become a Tea Party supporter five years later. We can also account for multiple influences simultaneously — isolating the impact of one factor while holding others constant.

Our analysis casts doubt on the Tea Party’s “origin story.” Early on, Tea Partiers were often described as nonpartisan political neophytes. Actually, the Tea Party’s supporters today were highly partisan Republicans long before the Tea Party was born, and were more likely than others to have contacted government officials. In fact, past Republican affiliation is the single strongest predictor of Tea Party support today.

What’s more, contrary to some accounts, the Tea Party is not a creature of the Great Recession. Many Americans have suffered in the last four years, but they are no more likely than anyone else to support the Tea Party. And while the public image of the Tea Party focuses on a desire to shrink government, concern over big government is hardly the only or even the most important predictor of Tea Party support among voters.

So what do Tea Partiers have in common? They are overwhelmingly white, but even compared to other white Republicans, they had a low regard for immigrants and blacks long before Barack Obama was president, and they still do.

More important, they were disproportionately social conservatives in 2006 — opposing abortion, for example — and still are today. Next to being a Republican, the strongest predictor of being a Tea Party supporter today was a desire, back in 2006, to see religion play a prominent role in politics. And Tea Partiers continue to hold these views: they seek “deeply religious” elected officials, approve of religious leaders’ engaging in politics and want religion brought into political debates. The Tea Party’s generals may say their overriding concern is a smaller government, but not their rank and file, who are more concerned about putting God in government.

This inclination among the Tea Party faithful to mix religion and politics explains their support for Representative Michele Bachmann of Minnesota and Gov. Rick Perry of Texas. Their appeal to Tea Partiers lies less in what they say about the budget or taxes, and more in their overt use of religious language and imagery, including Mrs. Bachmann’s lengthy prayers at campaign stops and Mr. Perry’s prayer rally in Houston.

In short, the tea-party is nothing but a new name for the same old right-wing bigots who have opposed every socially progressive policy since the Civil Rights act! The same bigots who wanted to make sure black people could not vote, live in their neighborhoods, or attend their schools, now oppose a black president. The same right-wing religious extremists who want Genesis taught in their kids' biology courses and think America should be a nation for Christians only, now want Michelle Bachmann to lead their country.

Enough nonsense! There is no such thing as the tea-party; it's just the same far right cranks and loons we've had to deal with for a very long time. So let's do what you ought to do with such quacks: let them rant and rave like the madmen they are, and ignore their wild chants when we actually sit down as rational people to attempt policy.

It's time to throw the tea-bag in the trash.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Jesus: Proclaimer of the Now and Future Kingdom

[Q]ueries concerned with whether the kingdom had come, was on the way, or would come later, must be irrelevant. At issue in New Testament eschatology is the actual movement itself of turning back, of entering into the kingdom. It is in the surrender of the self to God's will that his sovereignty is realized on earth (Jesus in his Jewish Context, 35).

In the teaching of Jesus the emphasis is not upon a future for which men must prepare, even with the help of God; the emphasis is upon a present which carries with it the guarantee of the future (Rediscovering the Teaching of Jesus, 205).

[Jesus called others] to do exactly what he himself was doing: heal the sick, eat with the healed, and demonstrate the kingdom's presence in that reciprocity and mutuality. It is not, he said, about intervention by God, but about participation with God. God's Great Cleanup of the World does not begin, cannot continue, and will not conclude without our divinely empowered participation and transcendentally driven collaboration (The Greatest Prayer, 90).

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Touching the Eternal

For none of us lives unto himself,and no one dies unto himself.For if we live, we live unto the Lord;and if we die, we die unto the Lord.Therefore whether we live or diewe are the Lord's (Romans 14: 7-8).

Monday, May 30, 2011

Bill Moyers on Memorial Day

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

Reflections of Eternal Life: Part 1

Thursday, May 19, 2011

Dissertation Defense : Videos of the Questions and Answers Round 1

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Spinoza's theory of individuals: Video of my dissertation defense

Introduction

Spinoza speaks often of individuals. Indeed, the well-being of a particular set of individuals, namely human individuals, is the principal focus of his philosophy. Naturally we expect such a systematic philosopher as Spinoza to provide a theory about what, precisely, an individual is. This expectation is bound to be present with regard to any philosopher who stresses the importance of individuals. For Spinoza, however, the problem is particularly acute, for he famously argues that there is only one substance, one self-existent being. If there is only one substance, it seems to follow that there is only one individual. Since substance in the western philosophical tradition is ordinarily restricted to particular individuals, this seems to be a sensible conclusion. It thus appears that Spinoza would conclude that there is only one individual. He does not do this, however. He repeatedly speaks of individuals in the plural, in particular of human individuals and their well-being. It is obvious that Spinoza holds that there are multiple individuals. Since he holds that there are many individuals but only one substance, it follows that most individuals are not substances. This invites the question of what an individual is for Spinoza.

In this study, my principal concern is to answer the question of what Spinoza holds an individual to be. My secondary aim is to argue that Spinoza's conception of an individual has important moral and political consequences regarding the nature of the state and the role of the community in the life of the individual.

I will present my reading of what an individual is for Spinoza and the moral and political implications that follow from his conception of individuals over the course of five chapters. Chapter 1 will argue for and explain my reading of Spinoza's system as a whole. We cannot begin to understand Spinoza’s conception of an individual without a firm grasp of the nature of his larger metaphysical system. This means that we must first clarify Spinoza’s central metaphysical concepts. These concepts are principally found in Ethics 1 and 2. They include the concepts of substance, attributes, and modes, as well as the central ideas which Spinoza offers on the relationship of the mind to the body, and his argument for universal casual determinism. A thorough investigation of Spinoza’s conception of the individual requires an adequate comprehension of these concepts.

In my second chapter, I will look closely both at Spinoza's primary texts for his understanding of what an individual is and at the work of leading interpreters on this aspect of his thought. The critical issue that I will examine in chapter 2 is what exactly counts as an individual for Spinoza. Although this issue, for reasons that will be presented, cannot be fully resolved, I will venture some conclusions about the origins of Spinoza's account of individuals and what he considers to be paradigmatic individuals.

Chapter 3 proceeds from the doctrine of individuals in general to a particular application of that doctrine. My focus here will be on whether or not the state (or “civil society”) counts as an individual. This question is important because Spinoza claims that the human individual is part of some larger individual, though he never explicitly says what this larger individual is. Since, for Spinoza, to be part of a larger individual is to have one's very nature determined by that individual, it is absolutely critical to determine what that individual is. In this chapter, therefore, I will carefully examine the work of Alexandre Matheron and his critics, primarily Steve Barbone and Lee Rice. Matheron argues that Spinoza thinks of a civil society as a kind of individual of which human beings are a part. Rice and Barbone argue against Matheron's reading.

In chapter 4, I will shift my analysis to the moral and political implications that follow from Spinoza's understanding of what an individual is. I will argue that Spinoza, contrary to some common readings of him, is not an egoist. Spinoza is not an egoist because his conception of individuals is primarily a relational one; whereas egoism, I will argue, depends upon a non-relational theory of individuals. To demonstrate this contrast between a relational and non-relational understanding of individuals and its role in interpreting Spinoza's position, I will carefully examine the work of feminist scholars who have written extensively on this issue. I will also contrast the work of these thinkers with the contribution of Rice.

Chapter 5 will briefly examine some political implications for Spinoza's theory of the individual. In particular, I will argue that Spinoza's understanding of the individual requires a strong commitment to what is often called “the welfare state.” To illustrate his commitment to a strong welfare state, I will argue, on the basis of his general political theory and several key texts, that Spinoza would support universal health care coverage.

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Spinoza: The Movie

The film does not present a very deep or even an entirely accurate understanding of Spinoza's philosophy. But presenting Spinoza as "the Apostle of Reason," weeping, cringing, screaming, and feebly coughing blood as tuberculous saps his life away, makes for interesting viewing.

As he implores all those around him to think rationally and live honestly, the irrational fanaticism of his society grows more violent, more deceptive, and ever less sane.

As you watch (it's only 52 mins long) pay special attention to the angry mob and Spinoza's reaction to their ways.

Here's the film:

Thursday, March 10, 2011

How to Become a Teacher...: Preface: A Change of Plans

Saturday, March 5, 2011

Mr. Moore comes to Madison

Thursday, March 3, 2011

A Word about Unions

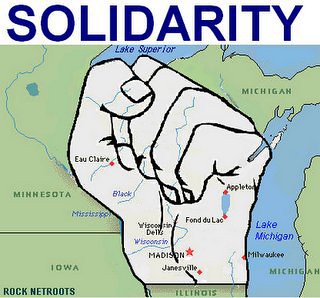

As the conflict in Wisconsin over Gov. Walker's proposal to strip unions of their right to collective bargaining continues, I find that many still do not understand what the debate is all about and why Walker's actions are terribly wrong and even deeply immoral.

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

Friday, February 18, 2011

The Battle for Wisconsin: What's happening and why

What's Happening in Wisconsin: Explained

— By Andy Kroll

| Fri Feb. 18, 2011 3:30 PM PSTActivists protesting new GOP Gov. Scott Walker's anti-union proposals have occupied the rotunda of the Wisconsin capitol building in Madison for the past week, but Walker is pressing ahead anyway.Flickr/Peter Gorman.

If you need to know the basics of what's going on in Wisconsin, read on. If you're already up to speed, you can follow the action on Twitter or jump straight to today's updates from our reporter on the ground in Madison.

—With additional reporting by Nick Baumannand Siddhartha Mahanta

The basics:

For days, demonstrators have been pouring into the streets of Madison, Wisconsin—and the halls of the state's Capitol building—to protest rookie Republican Governor Scott Walker's anti-union proposals. Big national unions, both major political parties, the Tea Party, and Andrew Breitbart are already involved. Democratic state senators have fled the state to prevent the legislature from voting on Walker's proposals. And the protests could soon spread to other states, including Ohio [....]

What's actually being proposed?

Walker says his legislation, which would strip most state employees of any meaningful collective bargaining rights, is necessary to close the state's $137 million budget gap. There are a number of problems with that argument, though. The unions are not to blame for the deficit, and stripping unionized workers of their collective bargaining rights won't in and of itself save any money. Walker says he needs to strip the unions of their rights to close the gap. But public safety officers' unions, which have members who are more likely to support Republicans and who also tend to have the highest salaries and benefits, are exempted from the new rules. Meanwhile, a series of tax breaks and other goodies that Walker and the Republican legislature passed just after his inauguration dramatically increased the deficit that Walker now says he's trying to close. And Wisconsin has closed a much larger budget gap in the past without scrapping worker organizing rights.

What's really going on, as Kevin Drum has explained, is pure partisan warfare: Walker is trying to de-fund the unions that form the backbone of the Democratic party. The unions and the Democrats are, of course, fighting back. The Washington Post's Ezra Klein drops some knowledge [emphasis added]:

The best way to understand Walker's proposal is as a multi-part attack on the state's labor unions. In part one, their ability to bargain benefits for their members is reduced. In part two, their ability to collect dues, and thus spend money organizing members or lobbying the legislature, is undercut. And in part three, workers have to vote the union back into existence every single year. Put it all together and it looks like this: Wisconsin's unions can't deliver value to their members, they're deprived of the resources to change the rules so they can start delivering value to their members again, and because of that, their members eventually give in to employer pressure and shut the union down in one of the annual certification elections.

You may think Walker's proposal is a good idea or a bad idea. But that's what it does. And it's telling that he's exempting the unions that supported him and is trying to obscure his plan's specifics behind misleading language about what unions can still bargain for and misleading rhetoric about the state's budget.

Walker's proposals do have important fiscal elements: they roughly double health care premiums for many state employees. But the heart of the proposals, and the controversy, are the provisions that will effectively destroy public-sector unions in the Badger State. As Matt Yglesias notes, this won't destroy the Democratic party. But it will force the party to seek funding from sources other than unions, and that usually means the same rich businessmen who are the main financial backers for the Republican party. Speaking of which....

Who is Scott Walker?

Walker was elected governor in the GOP landslide of 2010, when Republicans also gained control of the Wisconsin state senate and house of representatives. His political career has been bankrolled by Charles and David Koch, the very rich, very conservative, and very anti-union oil-and-gas magnates. Koch-backed groups like Americans for Prosperity, the Cato Institute, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and the Reason Foundation have long taken a very antagonistic view toward public-sector unions. They've used their vast fortunes to fight key Obama initiatives on health care and the environment, while writing fat checks to Republican candidates across the country. Walker's take for the 2010 election: $43,000 from the Koch Industries PAC, his second highest intake from any one donor. But that's not all!:

The Koch's PAC also helped Walker via a familiar and much-used political maneuver designed to allow donors to skirt campaign finance limits. The PAC gave $1 million to the Republican Governors Association, which in turn spent $65,000 on independent expenditures to support Walker. The RGA also spent a whopping $3.4 million on TV ads and mailers attacking Walker's opponent, Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett. Walker ended up beating Barrett by 5 points. The Koch money, no doubt, helped greatly.

What are the Democrats and the unions doing to respond?

Well, they're protesting, obviously—filling the halls of the Capitol and the streets of Madison with bodies and signs. They're calling their representatives and talking about recalling Walker (who cannot be recalled until next January) or any of eight GOP state senators who are eligible for recall right now. Meanwhile, all of the Democratic state senators have left the state in an attempt to deny Republicans the quorum they need to vote on Walker's proposals, but if just one of them returns (or is hauled back by state troopers), the GOP will have the quorum they need. (Interestingly, the head of the state patrol in the father of the Republican heads of the state senate and house of representatives, who are brothers.) Finally, Wisconsin public school teachers have been calling in sick, forcing schools to close while teachers in over a dozen other school districts picket the capitol, plan vigils, and set up phone banks to try to block Walker's effort.

How could this spread?

Other Republican-governed states are trying to mimic Walker's assault on public employee unions. The GOP won a resounding series of state-level victories in high-union-density states in November. Now they can use their newly-won power to crack down on one of the Democrats' biggest sources of funds, volunteers, and political power. Plans are already under consideration in places like Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan.

Speaking of Ohio:

As Suzy Khimm outlined on Friday, an estimated 3,800-5,000 protestors came out in full fury in Columbus, Ohio, to vent their anger over a similar anti-union bill that would limit workers' rights to bargain for health insurance, end automatic pay increases, and infringe upon teachers' rights to pick their classes and schools. As in Wisconsin, both the Ohio state house and governor's mansion flipped from blue to red last year. "This has little to do with balancing this year's budget," former Governor Ted Strickland told the AP. "I think it's a power grab. It's an attempt to diminish the rights of working people. I think it's an assault of the middle class of this state and it's so unfair and out of balance."

How are conservatives working to support Walker?:

It was only a matter of time till the Tea Party got in on the action. Stephanie Mencimerreports that activists are bussing into Madison, and are "promising a massive counter-demonstration." The push is being led by American Majority, a conservative activist group that trains impressionable young foot soldiers to become state-level candidates (check out their ""I Stand With Scott Walker Rally" Facebook page). Founded by Republican operatives, the well-funded group (which, according to tax fillings, had a budget of nearly $2 million in 2009) gets much of its money from a group with ties to those adorable Koch brothers. Conservative media baron Andrew Breitbart will be leading the rally, and will be joined by presidential candidate Herman Cain and maybe—if we're lucky—Joe "The Plumber" Wurtzelbacher. Expect fireworks.

I wish to add to Mother Jone's analysis only this: The rights of workers in this country are under serious assault. This is an absolutely historical moment. If we fail, if Walker successfully destroys the unions in Wisconsin, we are headed back to the age of robber barons and unaccountable corporate power. We have already taken too many steps in that harmful and unjust direction. Not only must we stop walking toward such an abyss, it is time - NO LONG PAST TIME! - that we turned around and walked the other direction.